Why Your Stamps Aren’t Worth What the Catalogue Says

Recently, Nick Salter wrote an interesting article about how stamp catalogues often fail to reflect the real-world value of stamps in today’s market.1 He made a lot of good points about eBay’s growing influence, the rise of tools like the Stamp Market Index, and the slow, often inconsistent pace at which catalogue publishers update their values.

And first, let me own up to something: when I covered this topic on the Stamp Show Here Today podcast, I completely botched the attribution. Nick’s article was the one I was referencing and I accidentally credited it to someone else. So I am setting the record straight. Nick Salter wrote it and provided some interesting discussion points. And now I’d like to add my own two cents—well, maybe more than two thousand words’ worth—on the same topic, from a mostly U.S.-centric perspective.

Because this is a conversation that keeps coming up.

Catalogues Are Not Price Sheets—They’re Relative Guides

Here’s a truth many collectors don’t realize: most stamp catalogues are not meant to be precise pricing tools. They’re relative price guides. That means they pick a middle-grade condition (usually “Fine-Very Fine” or “Very Fine”), a middle-of-the-road market assumption, and give you a number that shows you how that stamp ranks against others in its set or series.

They’re not the coin market’s Blue Sheet or Grey Sheet, nor are they the Stamp Market Quarterly (SMQ). But you’d be surprised how often the Scott Catalogue ends up being treated like it is. It is the go to catalogue in most libraries across the country that many philatelic treasure hunter’s go to when trying to research their rare finds. Although now, eBay seems to be taking it’s place.

I can’t tell you how frustrating it is for both buyers and sellers when an heir wants to sell a collection and sees the Scott Catalogue value written down by the original collector. Some think that catalogue price is the actual market value. Others are more realistic—they figure a dealer needs to make some margin, so they expect maybe a 20% to 50% discount to cover expenses and profit.

The problem is, most of the time, that price isn’t close to reality. The vast majority of stamps will never sell anywhere near their full catalogue value.

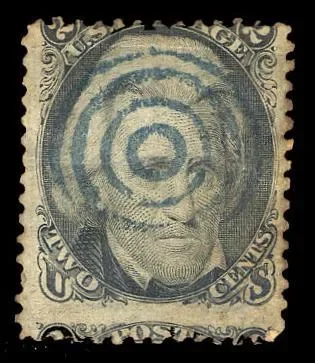

Take Scott #73 as an example. When I first started collecting, I seem to recall its used catalogue value was $35. Then it crept up to $40, then $50, and now it sits at $70. Yet the actual selling price hasn’t changed much in all that time—still about $5 for a stamp with minor faults and perhaps slightly off-center.

A typical #73 versus a high graded #73.

So, if the real market price has been flat, why has the catalogue value doubled over the past two or three decades? The answer is simple: the market has become bifurcated.

On classic U.S. stamps, there’s now a huge divide between clean, well-centered stamps and faulty, off-centered ones. Faulty and average-grade stamps have either stayed flat or even declined in price for 30–40 years. Meanwhile, nice, clean, well-centered stamps have kept pace with inflation and often trended upward.

At the higher grades—Extremely Fine and above—they’ve done even better. Many collectors today are far more condition-conscious. They’d rather buy one nice example than fill a space with a placeholder just to say it’s filled.

SMQ does its best to give a stamp a transactional value based on real auction results and verified trades. But even among its prices, there’s variation—especially with classic stamps. Why? Because the market is too nuanced to reduce to one number.

Take cancellations, for example. SMQ can’t possibly price every premium for a desirable strike. A neat, bold, well-placed cancel can bring a substantial premium, especially if the collector specializes in that city or is chasing auxiliary markings. A blurry, illegible smudge on the same stamp might sell for a fraction of the “catalogue” price.

The Gaps Between Data and Reality

During my time at PSE, I had many conversations with Scott, who assembles much of the SMQ data. His challenge is the same one catalogue editors have faced for over a century: you can only price what you can see.

If a stamp hasn’t sold publicly in a while, it’s a ghost. If the only recorded sale was a poorly timed auction during the summer doldrums, or from a second-tier auction house that doesn’t attract the right bidders, that “price” may be wildly misleading.

Worse, sales records don’t tell you about the items that didn’t sell—the stamps that linger because a seller refuses to accept a fair offer because it seems too low as a percentage of catalogue value, the high-demand items locked up in collections that never sell, the rarities that collectors would pay double for if they ever hit the market.

This is why so many catalogues have these frozen, zombie-like prices. Nick gave a perfect example: the 1889 President Soto Alfaro set from Costa Rica (Scott 25–34). Valued at $135.10 in 2009. Same in 2015. Same in 2020. Same in 2025. No inflation adjustment. No market reflection.

I actually know the person responsible for pricing many of the less active countries in the Scott Catalogue. He once told me that a lot of these countries haven’t seen price changes—not because the market hasn’t moved, but because no dealers are contributing updated information to Scott.

How strange is that? If you’re a dealer specializing in that country, why wouldn’t you want to help update the catalogue that almost everyone relies on?

He’s been assigned to tackle some of these underrepresented countries—the same kind Nick cites—and bring their prices up to date. But this is a slow process. He’s already several years in, and it may take a full decade before the updates are complete. And even then, if he is not able to find current pricing data, some of these sets will remain at their old price until a new price can be determined.

Enter eBay: Data at Critical Mass

The big game-changer has been eBay. Like it or not, eBay is now the single largest marketplace for stamps in the world, with over two million U.S. listings alone on any given day.

That’s over two decades of data—hundreds of millions of transactions. Enough to start showing real patterns.

The Stamp Market Index, a partnership between eBay and NobleSpirit, takes that data and turns it into a searchable database. And since 2004, it has recorded the sold prices of every auction and Buy-It-Now transaction. Want to know what a Mint Never Hinged 65¢ Graf Zeppelin actually sells for? Maybe 82 of them sold between $100 and $125 in the last year, that’s your real market, no matter what the catalogue says.

Want to know why you can never find a real Scott 348? The Index will tell you—maybe only a hand-full have come up for sale in five years. Suddenly that $45 catalogue value starts to look laughable.

This is the kind of transparency the hobby has long needed.

But Let’s Not Pretend eBay is Perfect

I use eBay data all the time. I think the Stamp Market Index is a fantastic step forward. But it’s not a perfect reflection of the market.

First, grading and descriptions on eBay are all over the map. Some sellers notoriously overgrade their stamps, a few even undergrade them, and plenty fail to mention faults altogether. That alone can skew the averages.

Then there’s the issue of photography. As I’ve written before, scanner placement matters. Move a stamp around the scanner bed and the centering looks different. Expand the scan slightly, and your brain stops being able to differentiate margin size. Our eyes are not good at processing ratios when margins get too large.

Digital compression can dramatically change how the stamp really looks. The stamp is compressed, decompressed and edited several times, first by the scanner, then by the eBay upload tool, before we ever see it on the screen. That’s assuming that no one every used an editing software to clean up the color or brighten the image.

And of course, visibility is a huge factor. If a seller doesn’t quite match your saved search terms, you’ll never see their listing. If you don’t know the seller exists, their stamps will sell cheap—and that “low” price goes into the database, pulling the average down.

Reputation matters too. Sellers with a history of careless descriptions or undisclosed faults often get punished by the market. Their lots sell for a discount, even when the stamp is better. That doesn’t mean the stamp is worth less; it means buyers don’t want the risk.

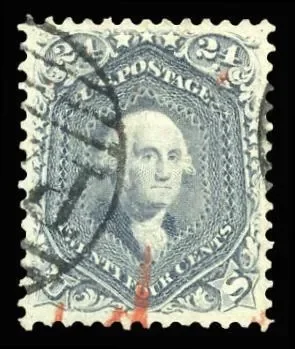

A Real Example: The Case of Scott 70b

Here’s one that drives me crazy: Scott 70b, the 24¢ Washington in the steel blue shade. I see it on eBay, often priced ridiculously low compared to its scarcity. Why? Because most buyers don’t trust the sellers to know the color. And frankly, they’re often right. The few times I have taken the bait and actually purchased the stamp uncertified on eBay resulted in a disappointing misidentification when the stamp arrives. Scanners butcher subtle shades. Screens display them differently. What looks like 70b on one monitor looks like a standard 78 on another.

So the market discounts them—unless they have a certificate. A certified 70b is a different story. It sells near its true value, often with a premium that reflects not just the authenticity, but the cost of the cert itself.

This happens all the time in currency too. A $10 note can sell for $50 simply because the grading fee was $25, and buyers are willing to pay a bit more for that assurance.

The Missing Half of the Market: What Doesn’t Sell

One of the biggest blind spots in both catalogues and eBay data is the silent market—the items that never sell because they’re priced too high, too poorly described, or simply never found by the right buyer.

If you’ve ever watched a high priced stamp sit unsold for years because the seller wants his standard percentage of Scott value, you’ve seen this in action. The demand is there, but at a much lower percentage of Scott. The price discovery never happens.

This is something the Stamp Market Index can’t fix. It can show you what sold, but it can’t show you the items that never sold, or the collectors waiting with cash in hand who just didn’t see the listing.

Why Catalogues Still Matter (and Should)

With all this said, I am not in the camp that wants to see catalogues disappear. Far from it. Catalogues serve a purpose no online database fully replicates: they give proportionality and context.

Open a Scott Specialized, and in seconds you can see which value in a set is the key. You can understand the hierarchy of a series, even if the individual numbers are off. That’s invaluable for beginners and experts alike.

But catalogues stop being useful when people treat them as hard pricing tools. “This is what Scott says, so that’s the price.” That’s how dealers justify sticking a $100 tag on something that’s been trading for $40 for a decade. It’s how collectors get frustrated and leave the hobby.

The Great Pricing Reset: Then and Now

Scott Catalogue

Nick reminded us of Scott’s dramatic pricing overhaul in 1988, when they slashed a massive portion of modern and common material to bring prices closer to reality. Some stamps dropped 30–70% overnight. Dealers were furious. Entire inventories were “devalued” instantly.

In hindsight, it was a mistake. Collectors and dealers had already been operating on a percentage of Scott’s listed values. So when Scott adjusted their numbers, it threw the entire market into chaos. Dealers who were known for selling at 80% of Scott suddenly watched their material freefall in perceived value. It took years for the collecting community to recover from that disruption.

Stanley Gibbons

Nick also pointed out that Stanley Gibbons is attempting a similar correction now. Their 2026 GB Concise catalogue is undergoing “the largest restructuring of prices in over 20 years,” with explicit reductions in inflated values. The difference this time is that they are warning the collecting community in advance. With enough time and education, perhaps this transition will be smoother.

Still, old habits die hard. What happens when you’ve built your business model around selling everything at a set percentage of catalogue value? Do you lower your percentage to match the new numbers—or do you bite the bullet and watch your margins erode?

The SMQ

The SMQ faced a similar challenge during the early days of stamp grading, around 2007. Bill Litle noticed that some modern issues were slipping in value—though in hindsight, it was likely that many of the early prices had simply been set too high, and the market was finally correcting itself.

He conducted a thorough review of the entire modern section, adjusting prices to match what stamps were actually trading for. The result? An implosion in that segment of graded stamps. Values dropped sharply, and the ripple effect was felt across the market and he was flooded with complaints from various dealers all over the country upset that he destroyed the market with a quick stroke of the pen.

It was a hard lesson, and one he didn’t repeat. From that point on, the SMQ became more cautious about major price revisions in that area. Today, collectors and dealers see the SMQ as a set of interdependent segments: modern stamps are priced at one percentage, earlier stamps at another, and adjustments are made more carefully based on population reports and actual demand.

My Take: Use All the Tools, Trust None Completely

Here’s my advice as someone who’s lived this from the inside: never rely on one source. Not Scott. Not SMQ. Not eBay or the Stamp Market Index.

Use catalogues for context. Use Scott for relative benchmarks. Use auction archives for serious pieces. Use eBay data for the pulse of the common market. And use your own experience—your eye, your comps, your understanding of demand—to make the final call.

Because the true price of a stamp is always the same: what a willing buyer will pay a willing seller, on the day the deal is made. Everything else is a guidepost.

https://classiclatinamerica.com/how-to-value-a-stamp/